SPLINTERS

Tennessee Valley Woodworkers

Vol. 19/ Issue 9

September 2004

Editor: Tom Gillard Jr.

Vol. 19/ Issue 9

September 2004

Editor: Tom Gillard Jr.

Meeting Notice:

The next meeting of the TN Valley Woodworkers

Will be held, September 21st at 7:00 p.m. in the

Duck River Electric Building, Dechard, TN

All interested woodworkers are invited!

The following people have agreed to serve as contacts for their particular

skills. If you have questions, suggestions for activities, or other

comments relating to these skills, please call these folks. Their

interest is to help the club better serve their area of expertise.

Your participation with them will help them achieve that goal.

Tom Cowan

967-4835 Design

Phil

Bishop 967-4626

Finishing

Tom Church 967-4460

Turning Harry

May 962-0215

Carving

Bob Reese

728-7974 Sharpening Ross

Roepke 455-9140 Jointery

Maurice Ryan 962-1555

Health and Safety

List of Club Officers

President: Ken

Gould

V. President: Barbara

Keen

Secretary: Chuck

Taylor

Treasurer: Henry

Davis

Publicity: Larry

Bowers

Webmaster: Richard

Gulley

Newsletter Editor: Tom Gillard

Jr.

Please remember, in your thoughts and prayers, all of the Military

Troops serving our country.

Calendar of Events:

Sept. 19-24: Coffee

County Fair

(click above to see features)

October 23rd: Phil Bishop Carving seminar

December 10th: TVW Christmas Party

The Coffee County Fair

is being held September 20-25. Our club will again set up in Morton Village.

Club members will man the Morton Village booth on Monday, Wednesday and

Thursday, beginning at 2pm. Friday and Saturday sessions will begin at

10am and will include the “Turning Bee”. Russ Willis and the guys

will be picking from 4 until 6, during the Friday session. The carvers

will also be presenting demonstrations at the booth, during some of the

sessions.

The club booth will not be open on Tuesday, since this

is the regular meeting night for our club.

Please bring items to display in our booth. Come and join the club and

have a relaxed time at the Fair.

The club contact for this event is Doyle

McConnell.

SHOW AND TELL

Bob Lowrance displayed a carving of an eagle

and flag he had made at John Campbell School. He also had a relief

carving of Pinocchio he had made for the Manchester Art display

Bill Davis brought an oak display

case, a box elder bowl and three

boxes. One was made from 4 different woods.

Jim Roy brought a nice spalted hackberry

bowl and a cherry footstool

with turned legs.

Ross Roepke had four more boxes

he had made for a charity auction. He also had a

table made from maple, mahogany and walnut. The finish was Deft.

Mary Ellen Lindsay brought the finished

caricature carving that she started during the last carving seminar.

Harry May brought a carving of three

dolphins. The wood was

Bradford pear that Ken Gould had given him.

Jim Van Cleave had four of six jewelry

boxes that he had made for cousins. They were made from cherry

and walnut. He encouraged people to bring things to show and tell.

David Whyte had a grinding station

that he had made. The inspiration came from Bob Reese’s grinding

seminar.

Maurice Ryan brought and discussed a replacement “hook and loop” for

a random orbit sander that he had found at Lowe’s. They can also

be found at supergrit.com

Ken Gould had a 1920 banjo that

came from Sears that he had reworked. He had also made a

fretless banjo of the 1830-1870 period. The wood was cherry, maple,

ebony and blackwood. The hide was from a deer that his father had

killed. Geoff Roehm played it for

him.

FOR SALE

Craftsman 10 inch Radial Arm Saw with leg set and new table top.

$350.00

Henry Davis, 393-3191

Refreshments were provided

by Bob Leonard and the Bowers. Thanks!!

Making Sense of Sandpaper

Final Part

The supporting role of backings and bonds

The backing's stiffness and flatness influence the quality and speed

of the sandpaper's cut. For the most part, manufacturers choose adhesives

and backings to augment the characteristics of a particular abrasive grit.

You will have a hard time finding an aggressive abrasive mineral, for example,

on a backing suited to a smooth cut.

The

stiffer the paper, the less the abrasive minerals will deflect while cutting.

They will cut deeper and, consequently, faster. Soft backings and bonds

will allow the abrasives to deflect more, giving light scratches and a

smooth finish. You must even consider what's behind the backing. Wrapping

the sandpaper around a block of wood will allow a faster cut than sanding

with the paper against the palm of your hand. For instance, an easy way

to speed up your orbital sander is by exchanging the soft pad for a stiff

one. The other consideration is the flatness of the backing, which has

nothing to do with its stiffness. Flat backings position the minerals on

a more even level so they cut at a more consistent depth, resulting in

fewer stray scratches and a smoother surface.

The

stiffer the paper, the less the abrasive minerals will deflect while cutting.

They will cut deeper and, consequently, faster. Soft backings and bonds

will allow the abrasives to deflect more, giving light scratches and a

smooth finish. You must even consider what's behind the backing. Wrapping

the sandpaper around a block of wood will allow a faster cut than sanding

with the paper against the palm of your hand. For instance, an easy way

to speed up your orbital sander is by exchanging the soft pad for a stiff

one. The other consideration is the flatness of the backing, which has

nothing to do with its stiffness. Flat backings position the minerals on

a more even level so they cut at a more consistent depth, resulting in

fewer stray scratches and a smoother surface.

Cloth is the stiffest but least-flat backing. It will produce the coarsest

and fastest cut. Cloth comes in two grades, a heavy X and a light J. Paper

is not as stiff as cloth but it's flatter. It comes in grades A, C,D, E

and F (lightest to heaviest). A-weight paper that has been waterproofed

is approximately equivalent to a B-weight paper, if one existed. Polyester

films, including Mylar, look and feel like plastic. They are extremely

flat and pretty stiff. They will give the most consistently even cut and

at a faster rate than paper.

The backings for hand sheets and belts are designed to flex around curves

without breaking. This is not true for sanding discs for random-orbit sanders.

They are designed to remain perfectly flat, and if used like a hand sheet,

the adhesive will crack off in large sections. This is called knife-edging

because the mineral and adhesive separated from the backing, form knife-like

edges that dig into and mark the work.

Adhesive bonds on modern sandpaper are almost exclusively urea- or

phenolic-formaldehyde resins. Both are heat-resistant, waterproof and stiff.

Hide glue is sometimes used in conjunction with a resin on paper sheets.

It is not waterproof or heat-resistant, but hide glue is cheap and very

flexible.

When this article was written, Strother Purdy was an assistant

editor of Fine Woodworking.

Photos: Strother Purdy; drawing: Tim Langenderfer

From Fine Woodworking #125, pp. 62-67

Taunton

press.com

Franklin County Library Request:

Tom McGill attended a preliminary meeting with the library and is working

on the sizes of the cabinets needed. They will be approximately 22

feet long. He will call a meeting of volunteers to decide how to

approach the project.

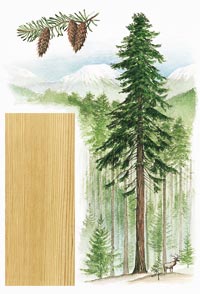

Wood Profile - Douglas Fir

The globe-trotting he-man of American softwoods

Diaries claim that early loggers in what came to be Oregon and Washington

often felled 400'-tall trees, each containing enough high-grade lumber

to build seven houses! The lofty tree was the Douglas fir, and it still

dominates the great forests of the Pacific Northwest.

In 1827, English botanical explorer David Douglas recognized the fir's

resource potential. Hoping that the easily grown tree could adapt to his

country's reforestation efforts, he shipped seed cones from the Columbia

River basin back to the British Isles.

From that introduction, the fir found favor as fast-growing timber

first in England, then throughout western Europe. Now, even the adopted

habitats of Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa boast Douglas fir

forests.

Wood identification

In the U.S., Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) naturally ranges from

the Mexican border north to Alaska, and from the Pacific coast east to

the Rocky Mountains. Often found in pure stands, Douglas fir can attain

an average mature height of about 300' and diameters from 10' to 17'.

On older trees, the rough bark may be 12" thick. Younger trees have

a smooth bark with frequent blisters filled with a pungent resin.

Tiny winged seeds, released from cones as large as a man's fist, quickly

germinate in sufficient sunlight. Because of this, Douglas fir quickly

takes over and reforests burned or clearcut areas.

Douglas fir's pinkish-yellow to orange-red heartwood provides a distinct

contrast in the growth rings. On flatsawed boards and rotary cut veneer,

this translates to an abrupt color change. The thin band of sapwood is

often nearly pure white.

Working properties

In comparison to its weight, Douglas fir ranks as the strongest of

all American woods. It is also stiff, stable, and relatively decay resistant.

Douglas fir's coarse texture can't easily be worked with hand tools.

And to avoid tearing grain, even power tool blades must be sharp. Yet,

the wood grips nails and screws securely, and readily accepts all types

of adhesives.

Because Douglas fir contains fewer resins than many other softwoods,

count on success with paint and clear finishes. Staining, however, becomes

a

problem due to the light-to-dark variation between growth rings that causes

uneven coloration.

Uses in woodworking

Vast quantities of Douglas fir provide dimension lumber for the construction

industry and veneers for plywood. The wood's appearance and easy-working

properties have earned it a spot in the manufacturing of windows, doors,

and moldings.

Flatsawed, Douglas fir makes attractive, serviceable cabinets and paintable

furniture. Sawn as vertical grain, Douglas fir performs well as flooring

and looks stunning as cabinetry.

Cost and availability

Found across most of the nation as common construction lumber, Douglas

fir falls in the inexpensive price range of about $1 per lineal foot. However,

sawed for vertical grain and graded for "superior finish," the cost rises

by at least three times. Douglas fir plywood in all grades is readily available.

Illustration: Steve Schindler

Photographs: Western Wood Products Assn.

See you

on the 21st.

click on the image to go to these sites

Donations to the club have been made by these companies.

Thanks,

Vol. 19/ Issue 9

September 2004

Editor: Tom Gillard Jr.

Vol. 19/ Issue 9

September 2004

Editor: Tom Gillard Jr.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()