SPLINTERS

Tennessee Valley Woodworkers

Vol. 19/ Issue 7

July 2004

Editor: Tom Gillard Jr.

Vol. 19/ Issue 7

July 2004

Editor: Tom Gillard Jr.

Meeting Notice:

The next meeting of the TN Valley Woodworkers

Will be held, July 19th at 7:00 p.m. in the

Duck River Electric Building, Dechard, TN

All interested woodworkers are invited!

The following people have agreed to serve as contacts for their particular

skills. If you have questions, suggestions for activities, or other

comments relating to these skills, please call these folks. Their

interest is to help the club better serve their area of expertise.

Your participation with them will help them achieve that goal.

Tom Cowan

967-4835 Design

Phil Bishop

967-4626 Finishing

Tom Church 967-4460

Turning Harry

May 962-0215

Carving

Bob Reese

728-7974 Sharpening Ross

Roepke 455-9140 Jointery

Maurice Ryan 962-1555

Health and Safety

List of Club Officers

President: Ken

Gould

V. President: Barbara

Keen

Secretary: Chuck

Taylor

Treasurer: Henry

Davis

Publicity: Larry

Bowers

Newsletter Editor: Tom Gillard

Jr.

Calendar of Events:

July 24th: Bob Reese's sharpening

workshop

October 23rd: Phil Bishop Carving seminar

December 10th: TVW Christmas Party

SHOW AND TELL

Bob Lowrance displayed carvings that he had started while attending

the John Campbell School. The carvings were of cowboys

and had a lot of intricate detailing.

Harold Hewlegy brought some tools

that he had made. They included a mortising plane, a scraper plane

(blade made from a Datsun leaf spring) and a cabinet scraper. All the holders

were made from cherry.

Maurice Ryan brought pictures of a furniture repair job. He had started

from a “wreck” and the project consisted of rebuilding, repairing, and

refinishing the piece of furniture.

Tom Gillard displayed a cherry

box he had been requested to make. The box is to be used to hold the ashes

of a cremated pet.

Harvey Carter brought a “bear”

chair. This was his beginning woodworking project and was to be built

for a child. The plan was obtained from a magazine and was billed as a

“weekend” project. He told the story of the project lasting for 5 years

and when he was finished, the child had outgrown the chair.

Don Powers brought a piece of chettum

wood mounted on a cherry base. The natural chettum

made an attractive display.

Kenneth Clark brought a walnut

table that he had made and finished with sanding sealer and gloss varnish.

Geoff Roehm showed a picture of his current project. He is installing

a CNC milling machine in his shop to make the intricate fixtures used in

his guitar manufacturing.

Henry Cox brought 3 scroll saw projects with intricate detailed cuts.

He also gave members a tip to keep scroll saws from vibrating so much.

He had made a large box for mounting the scroll saw and filled the box

with sand to reduce the vibration of the saw.

IN REMBRENCE

Bernie Kollstadt

has passed away. Henry will be sending a gift in his name to the Library

in Tullahoma. Roberta's address is 3008 Tara Blvd, Tullahoma,

TN 37388. If you want to send a card.

His daughter has told me more than once that Bernie really enjoyed

the Wood Club. It is a club that he wishes he could have found much

earlier.

Making Sense of Sandpaper

Knowing how it works is the first step in choosing the right abrasive

by Strother Purdy

Years ago at a garage sale, I bought a pile of no-name sandpaper for

just pennies a sheet. I got it home. I sanded with it, but nothing came

off the wood. Sanding harder, the grit came off the paper. It didn't even

burn very well in my wood stove.

Sanding is necessary drudge work, improved only by spending less time

doing it. As I learned, you can't go right buying cheap stuff, but it's

still easy to go wrong with the best sandpaper that's available. Not long

ago, for example, I tried to take the finish off some maple flooring. Even

though I was armed with premium-grade, 50-grit aluminum-oxide belts, the

work took far too long. It wasn't that the belts were bad. I was simply

using the wrong abrasive for the job. A 36-grit ceramic belt would have

cut my sanding time substantially.

The key to choosing the right sandpaper is knowing how the many different

kinds of sandpaper work. Each component, not just the grit, contributes

to the sandpaper's performance, determining how quickly it works, how long

it lasts and how smooth the results will be. If you know how the components

work together, you'll be able to choose your sandpaper wisely, and use

it efficiently. Then you won't waste time sanding or end up burning the

stuff in your wood stove.

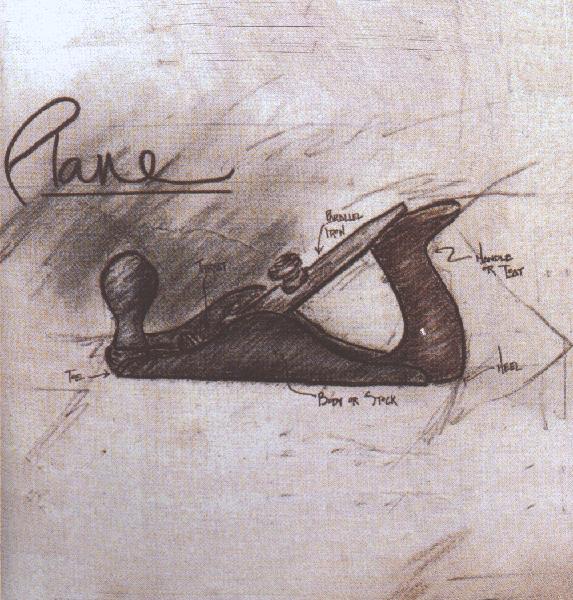

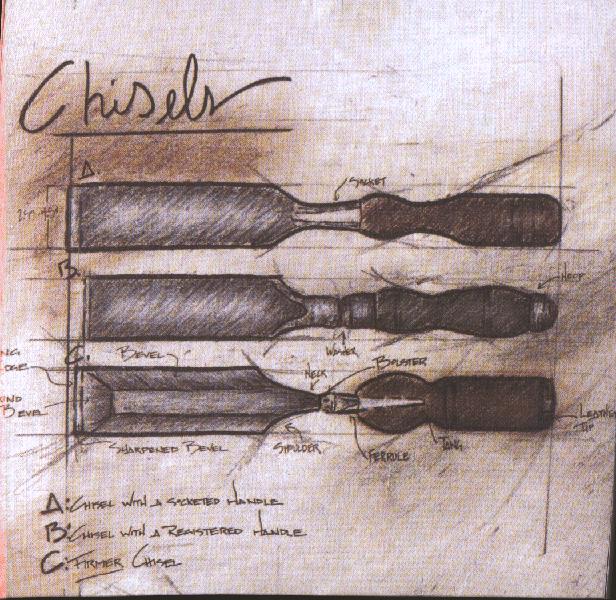

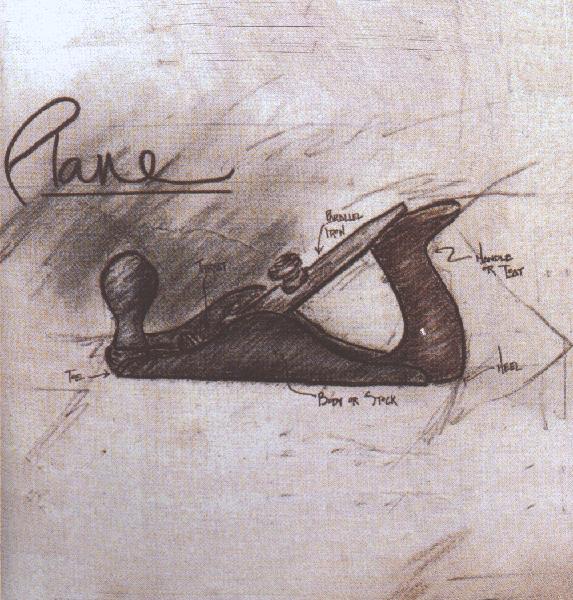

Sandpaper is a cutting tool

What sandpaper does to wood is really no different from what a saw,

a plane or a chisel does. They all have sharp points or edges that cut

wood fibers. Sandpaper's cutting is simply on a much smaller scale. The

only substantial difference between sandpaper and other cutting tools is

that sandpaper can't be sharpened.

Sandpaper is made of abrasive minerals, adhesive and a cloth, paper

or polyester backing. The abrasive minerals are bonded to the backing by

two coats of adhesive; first the make coat bonds them to the backing; then

the size coat locks them in position.

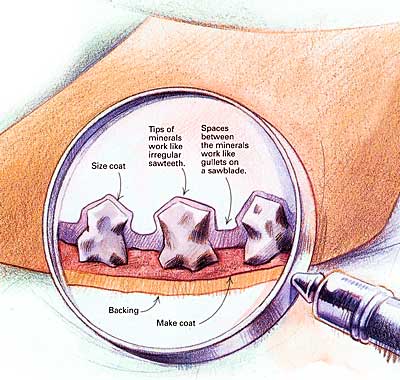

Look at sandpaper

up close, and you'll see that the sharp tips of the abrasive grains look

like small, irregularly shaped sawteeth. The grains are supported

by a cloth or paper backing and two adhesive bonds, much the way that sawteeth

are supported by the sawblade. As sandpaper is pushed across wood, the

abrasive grains dig into the surface and cut out minute shavings, which

are called swarf in industry jargon. To the naked eye, these shavings look

like fine dust. Magnified, they look like the shavings produced by saws

or other cutting tools.

Look at sandpaper

up close, and you'll see that the sharp tips of the abrasive grains look

like small, irregularly shaped sawteeth. The grains are supported

by a cloth or paper backing and two adhesive bonds, much the way that sawteeth

are supported by the sawblade. As sandpaper is pushed across wood, the

abrasive grains dig into the surface and cut out minute shavings, which

are called swarf in industry jargon. To the naked eye, these shavings look

like fine dust. Magnified, they look like the shavings produced by saws

or other cutting tools.

Even the spaces between the abrasive grains serve an important role.

They work the way gullets on sawblades do, giving the shavings a place

to go. This is why sandpaper designed for wood has what's called an open

coat, where only 40% to 70% of the backing is covered with abrasive. The

spaces in an open coat are hard to see in fine grits but are very obvious

in coarse grades.

Closed-coat sandpaper, where the backing is entirely covered with abrasive,

is not appropriate for sanding wood because the swarf has no place to go

and quickly clogs the paper. Closed-coat sandpaper is more appropriate

on other materials such as steel and glass because the particles of swarf

are much smaller.

Some sandpaper is advertised as non-loading, or stearated. These papers

are covered with a substance called zinc stearate -- soap, really -- which

helps keep the sandpaper from clogging with swarf. Stearated papers are

only useful for sanding finishes and resinous woods. Wood resin and most

finishes will become molten from the heat generated by sanding, even hand-sanding.

In this state, these substances are very sticky, and given the chance,

they will firmly glue themselves to the sandpaper. Stearates work by attaching

to the molten swarf, making it slippery, not sticky, and preventing it

from bonding to the sandpaper.

Methods for sanding efficiently

Sanding a rough surface smooth in preparation for a finish seems a

pretty straightforward proposition. For a board fresh out of the planer,

woodworkers know to start with a coarse paper, perhaps 80-grit or 100-grit,

and progress incrementally without skipping a grade up to the finer grits.

At each step, you simply erase the scratches you made previously with finer

and smaller scratches until, at 180-grit or 220-grit, the scratches are

too small to see or feel. But there are a fair number of opinions on how

to do this most efficiently.

Don't skip grits, usually -- Skipping a grit to save time and sandpaper

is a common temptation, but not a good idea when working with hardwoods.

You can remove the scratches left by 120-grit sandpaper with 180-grit,

but it will take you far more work than if you use 150-grit first. You

will also wear out more 180-grit sandpaper, so you don't really save any

materials. When sanding maple, for instance, skipping two grits between

80 and 180 will probably double the total sanding time. This, however,

is not as true with woods such as pine. Soft woods take much less work

overall to sand smooth. Skipping a grit will increase the work negligibly

and may save you some materials.

(The

Taunton Press)

The speaker will be Glenn Lazalier who was Chief Engineering Officer

for Arnold Engineering Development Center support contractor. He

is now retired and one of his hobbies is woodworking. He will talk

about the king-size Walnut sleigh bed he built as a wedding gift for his

daughter. He also has carved delicate miniatures of human and animal

figures. He has crafted many large furniture pieces.

See you on the 20th.

click on the image to go to these sites

Vol. 19/ Issue 7

July 2004

Editor: Tom Gillard Jr.

Vol. 19/ Issue 7

July 2004

Editor: Tom Gillard Jr.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()