SPLINTERS

Tennessee Valley Woodworkers

Vol. 18/ Issue 10 October

2003 Editor: Tom Gillard Jr.

Vol. 18/ Issue 10 October

2003 Editor: Tom Gillard Jr.

Meeting Notice:

The next meeting of the TN Valley Woodworkers

Will be held, October 21st, at 7:00 p.m. in the

Duck River Electric Building, Dechard, TN

All interested woodworkers are invited!

The following people have agreed to serve as contacts for their particular

skills. If you have questions, suggestions for activities, or other

comments relating to these skills, please call these folks. Their

interest is to help the club better serve their area of expertise.

Your participation with them will help them achieve that goal.

Design: Alice

Berry

454-3815

Finishing: Phil

Bishop

967-4626

Turning: Tom

Church

967-4460

Carving: Harry

May 962-0215

Sharpening:

Bob

Reese

728-7974

Joinery: Ross

Roepke 455-9140

Health and Safety:

Maurice

Ryan 962-1555

List of

Club Officers

President: Doyle

McConnell

V. President: Ken

Gould

Secretary: Barbara

Keen

Treasurer: Henry

Davis

Publicity: Loyd

Ackerman

Newsletter Editor Tom Gillard

Jr.

GOD BLESS AMERICA!

Please remember, in your thoughts and prayers, all our Troops heading

for the Middle East.

FOR MEMBERS ONLY

Don't forget about the club give-away this year.

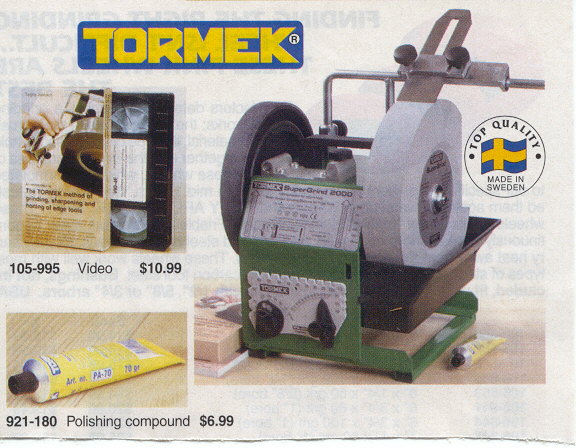

We have a Tormek sharpening machine for some lucky winner at the Christmas

party.

October Program:

STEVE SHORES WILL BE DOING A PROGRAM ON THE BIRD HOUSE AS A CHRISTMAS ORNAMENT

- THIS WILL BE A LEAD INTO THE SATURDAY SEMINAR OF TURNED ORNAMENTS

THAT HE WILL BE DOING.

Fall Symposium Registration

October 25, 2003

The Tennessee Valley Woodworkers Club is sponsoring a woodturning symposium

on October 25, 2003. The symposium will accommodate the needs of

all levels of woodturners by splitting the first session of the day into

Basic Woodturning and Advanced Woodturning. The Basic session is for those

with little or no experience in woodturning. The Advanced session is for

the more experienced turners. Beginning the day with a split session will

help us prepare the most basic turners to enjoy the remainder of the day

while serving more experienced turners appropriately. After the split session,

we will all convene together for the remaining sessions.

We will hold the symposium at Tom Cowan’s shop near Winchester.

Click HERE

for the information packet and HERE

for the registration form.

SHOW & TELL

Harry May brought a carving of an Indian

face finished with Johnson’s paste wax. He also noted that he

had received several commissions for other carvings.

Ken Gould brought a blanket chest

made of cherry and quarter sawn oak

that he had made as a wedding gift for one of his children.

Geoff Roehm brought in one

of his beautiful guitars.

Ed White showed a sawhorse

that he had made, explaining the construction techniques used to assemble

the stackable sawhorses.

Tom Gillard brought pictures of dressers

made for his boys along with sailboats

made as gifts for the Oldham company.

David White brought in a twisted

walking stick. He did add some cherry

and walnut to it to give it some character.

Bob Reese told the club about the adaptation of a newel

post into a lamp. The post was from the 1830’s and had been in

his wife’s ancestral home. He also showed the jig he constructed

to help when making the dovetail slots

on the base for the feet and a steady-rest

to

assist in the turning operations.

Doyle McConnell showed one of the jewelry

boxes he made with a book-matched

top of spaulted maple.

Gary Runyon shared the depth gauge

that

he had made.

Hugh Hurst showed a beautiful walnut

bowl with Deft Oil finish, followed with lacquer. He also brought

a box elder flat bowl with a textured

edge.

Chuck Taylor brought a veteran’s

memorial flag case made of oak, with finger joint construction.

Also, clocks and baby rattles that he had made as gifts to be carried on

a mission trip to Russia.

Jim Parker displayed his cherry

three-drawer chest with a raised panel back that he had finished with

2:1 red oak and mahogany stain and topped with satin finish polyurethane.

It had hand cut dovetail drawers.

Ray Torstenson did the program

on bandsaw boxes and brought in

a few samples of his work.

Message from the editor:

Speaking of the Oldham Company. They have a company benevolence fund

to help support employees who are having financial troubles. Some

of the money is loaned and some is given, with no payback expected. In

order to raise money, Oldham either sales some of their own products or

they have an auction of donated items. These sales are internal,

no outsiders allowed. That is what my ‘boat’ went for.

This is where the club comes in. If anyone would like

to make an item or two and donate it to this cause, I’ll collect them and

ship them to my, and your, good friend Paul at Oldham. This sounds

like a VERY good cause and it is a way for the employees of Oldham

to help one another. It is a way for us, the club, to say thanks

to Oldham for all the items sent to us for give-a-ways at our picnics and

Christmas parties.

Thanks, Tom Gillard

Lignum Vitae

At home in water, lignum vitae helped submarines run quietly.

An explosion rocked the humid night. Thrown to the deck, the young

Confederate crewman escaped the projectiles flying everywhere. But not

all hands were as lucky. Glancing into the boiler room, he found the first

mate lying still. Was it a mortar shell that had felled him? It couldn’t

be; they were alone on the ocean.

The blow that struck the Confederate cruiser Georgia on that fateful

evening in 1864 came from no enemy gunner. Instead, the awesome burst and

devastating shrapnel was from shattering wood.

During the early days of oceangoing steamships, shipyards made many

engine cogs and shafts of lignum vitae, an iron-tough wood so heavy it

sinks in water. Unfortunately, crews found out that the wood also comes

apart under extreme pressure when combined with more than 150° heat—as

was created in the engine room when the Georgia mate stoked the fire through

the open boiler door.

Incidences such as this caused shipbuilders to abandon lignum vitae

in machinery aboard surface vessels. However, because sea water naturally

lubricates the wood, lignum vitae was adopted as the material for silent-running

propeller shaft bearings in submarines and has only recently been displaced

by space-age substances.

Above sea level, lignum vitae’s remarkable hardness made it perfect

for chopping blocks, block-and-tackle assemblies, and casters. Early woodworking

tool manufacturers relied on the wood for mallets, plane soles, and bandsaw

guide blocks. And, should you happen on a bowling ball from the 1800s,

expect that it, too, will be rollable, rockhard lignum vitae.

WOOD On-line

Illustration: Jim Stevenson

OLD TOOLS

In the 19th century, America was on the move. Commerce, industry, and

agriculture, fueled by the young nation’s growth and westward expansion,

rolled ceaselessly onward, carried by countless wooden wheels.

Wheelwrights were riding high then, building spoked wooden wheels for

everything from army artillery to Park Avenue hansom cabs. Strong joints

were crucial because, as you’ll recall from many a western movie, some

of those wheels took terrific abuse.

In particular, a lot of force came to bear at the outer ends of the

spokes, where they connected with the felloes, the arc-shaped segments

that made up the outer rim of the wheel. (There were normally two spokes

for each felloe.) Standard practice called for mating a round tenon on

the end of the spoke with a hole bored into the felloe. Craftsmen often

formed the tenon with a device somewhat like a plug cutter, a tool known

as a hollow auger.

Both wooden and iron hollow augers had been in use in America since

the time of the Revolution. The wooden one shown above (no. 1) is typical

of the early, non-adjustable style. Its two steel blades cut a 3/4"-diameter

tenon.

Then, in 1829, Abel Conant of Pepperville, Massachusetts, received the

first United States patent for a hollow auger. For decades after, tinkerers

and toolmakers alike buckled down to devising, patenting, and marketing

improved devices to cut cylindrical tenons. By December 5, 1911, when the

last patent was issued for a hollow auger, 85 styles had been patented.

Made to fit in a bitstock or brace, the devices appealed to chairmakers,

laddermakers, and other craftsmen as well as wheel-wrights. With a hollow

auger, a sturdy joint could be made in two relatively simple operations.

And, with a means of cutting the tenons uniformly, parts could be made

in a batch rather than being individually hand-fitted.

Variations among hollow augers generally involved methods of setting

the diameter of the tenon. Some cut fixed standard sizes, others were adjustable.

Some models were amazingly complex, verging on the impractical. Those didn’t

last long in the marketplace.

Hollow augers themselves couldn’t survive the decline of wheelwrighting.

As steel wheels drove out wooden ones in the years following World War

I, demand for hollow augers flagged. Fewer and fewer were available. In

the late 1940s, the few remaining models disappeared from the market.

Tools from the collection of James E. Price, PhD., Naylor,

Missouri

Photograph: Hetherington Photography

Written by Larry Johnston

WOOD On-line

FOR SALE

Wood for Sale:

1 piece walnut 6" x 5" x 38", I paid $40, I'll take $40.

1 piece fiddleback maple 2 1/2" x 17" x 8 ft. $125.

Jim Van Cleave 455-8150

10 % OFF Fine Woodworking

Books from Taunton Press

…We’re open Monday thru Saturday

click on picture to visit Oldham

SEE YOU ON THE

21st!

Vol. 18/ Issue 10 October

2003 Editor: Tom Gillard Jr.

Vol. 18/ Issue 10 October

2003 Editor: Tom Gillard Jr.